News

Living Urbanism

Posted 31 08 2017

in News

Zoë Avery, Senior Planning, Urban and Landscape Design Consultant has been researching how we can better integrate living roofs

The uptake of living roofs, walls and facades is increasing globally as cities throughout the world begin to recognise the multitude of economic, social and environmental benefits for people, land, water, nature and visitors.

“When one creates green roofs the houses themselves become part of the landscape” -Freidensreich Hundertwasser (1928-2000)

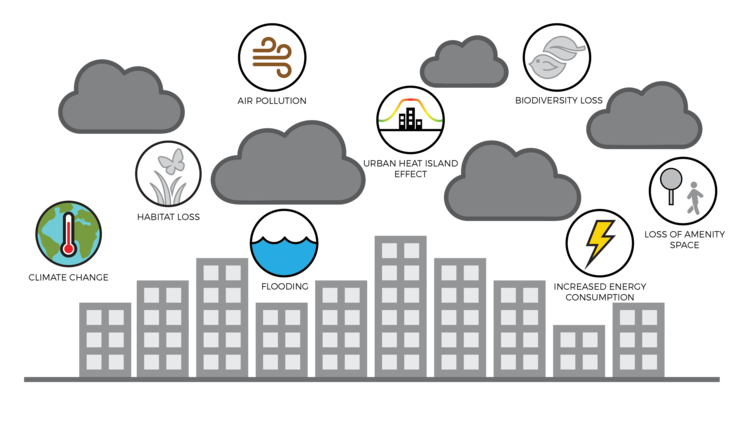

Many of our cities in Aotearoa face continued pressure from advancing urbanisation. 70% of our world’s population is estimated to be living in urban environments by 2050. Population growth, urban development and sprawl have altered once natural environments, creating increased built form, more hard surfaces, less green space and less permeable areas (Figure 1).

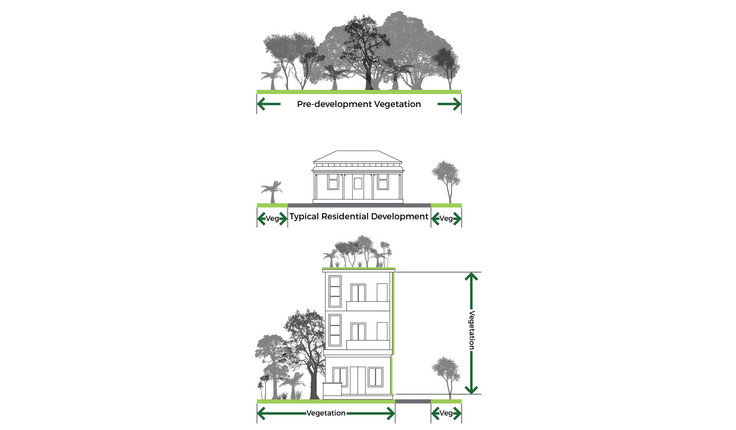

Over the last century, we have seen residential lot sizes reduced significantly while physical dwelling size has increased markedly, leaving less space for permeability, green space and habitat (Figure 2).

Zoë Avery, Senior Planning, Urban and Landscape Design Consultant at 4Sight Consulting has been researching how we can better integrate living roofs as urbanistic systems into our cities in light of urban population growth. The term ‘Living Urbanism’ is a concept developed to assist living roof design that results in maximised benefits. Living roofs, when designed in a holistic manner can produce multi-functional benefits that significantly improve our urban environment. Living roof design currently does not successfully maximise these potential benefits, nor are they acknowledged widely. Regularly, living roofs are designed for one benefit, for example stormwater attenuation or aesthetics. The resulting effect is a reduction in the perceived benefits and subsequently lower global uptake.

The creation of our urban environments with large areas of impermeable surfaces has resulted in less vegetation and habitat, more surface runoff and flash flooding. Urbanisation and the issues we face as a result of it require new ways of design-led thinking to make our cities more liveable. Around the world cities are prioritising the promotion, installation and uptake of green infrastructure.

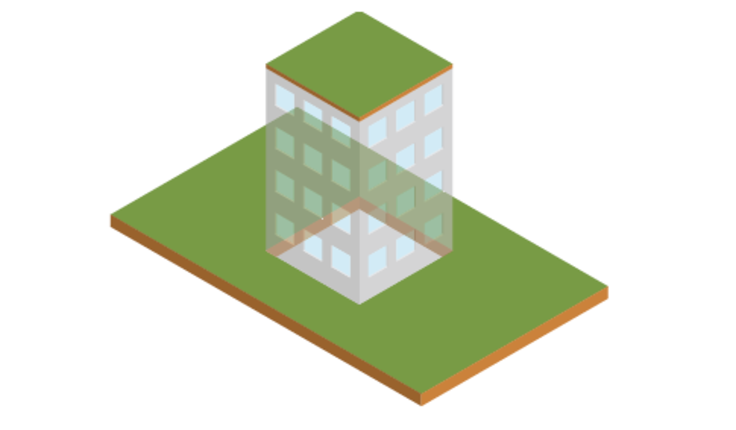

Living roofs, walls and facades are an integral green infrastructure system for any city as they do not require any space at the ground level (Figure 3) and can be retrofitted onto existing buildings.

Globally, living roofs, walls and facades are being used to mitigate the loss of vegetation in our urban environments, provide aesthetic green space, reduce stormwater runoff effects and enhance biodiversity.

Living roofs, commonly referred to as green roofs, are intentionally vegetated roofs and have been around since humans first built shelters. However, the approach and initiative required to implement them in our modern environment is new, and lack of local information and experience has been a barrier to living roof development in New Zealand (NZ).

Living Urbanism is the study of the characteristic ways of interaction of inhabitants of urban areas with green infrastructure and the built environment.

Amid concerns about climate change adaptation, energy conservation, food production and our ability to develop sustainably, there is a need to pursue solutions that present real economic, environmental and social benefits within our built environments.

Living roofs offer just such an opportunity and shape how we view ecology in cities by shifting the focus to exploring what our cities would look like if the above benefits were embedded in the design process and functional interventions that shape our cities.

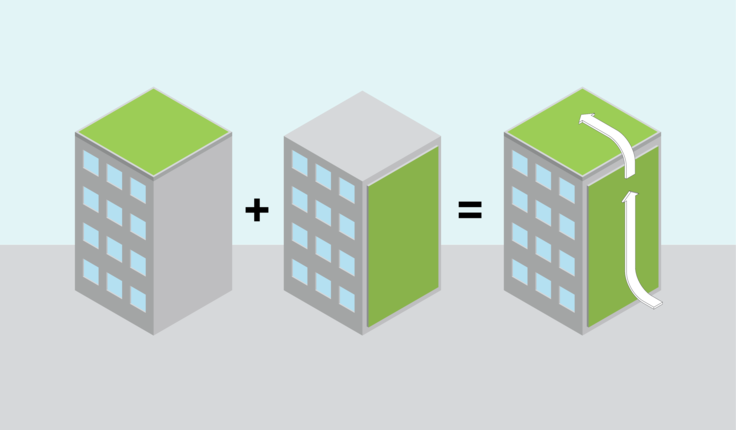

Figure 4: Connection of ground plane to living wall and living roof

The role of green technology interventions and the built environment in general (such as living roofs and walls) start to redefine the human role in integrating life processes into future city landscapes and in particular how our indigenous flora and fauna can play a part in these life processes – thus protecting and enhancing indigenous biodiversity resilience and sustainability in our cities.

Living roofs blend beauty and function, with an aesthetically appealing building technique and material that provides sanctuary for wildlife; detention and slow release of stormwater; reduction of urban heat island effect; and building insulation.

The multifaceted outcomes delivered by living roofs not only addresses non-human life within the city, but extends to engagement with human processes. This co-facilitation leads to a more resilient city providing for the inherent adaptability of city residents, both human and non-human in a changing world.

Currently, most living roof designs do not consider the roof space as an extension to the landscape, society and part of our urban environment, rather as a separate system with localised benefits - such as mitigating stormwater.

For various reasons living roofs are being designed as isolated systems and it is suggested that this has led to a loss in living roof value and opportunity.

‘Living Urbanism’ design practice aims to enable future living roof, living wall and green infrastructure developments to enhance our urban systems. This design practice includes acknowledged benefits and extends to incorporate the living and the non-living relationships that can enhance urbanism.

Living Urbanism is designed as a toolkit to maximize the amenity of living roofs and walls. Living Urbanism assists urban designers, architects, planners and developers with creating places where people, nature and the economy thrive. It is a toolkit that helps you explore all of the benefits that could be incorporated into your design.

Zoë has been working alongside Renee Davies, Dean of Unitec, to develop a Living Roof Guide for Whangarei – being the first living roof guide in New Zealand. This guide will be launched in a few weeks and aims to showcase the multi-functional benefits and design considerations of these systems. Living Roof benefits include stormwater attenuation, increased biodiversity, the ability to create more public spaces providing greater connection with nature, extending the roof life, increased marketability and profitability of the buildings to name a few. We will share the Living Roof Guide in the coming weeks.

Share

09 Mar

SoLA seminar series

The SoLA (School of Landscape Architecture at Lincoln University) seminar series comprises a range of expert-led talks that are scheduled …

09 Mar

Help Build the Young Landscape Architects Alliance

Calling students, recent graduates, and professionals within the first five years of practice in Landscape Architecture or related disciplines

Every strong professional community starts with a conversation. On 14 March, that conversation begins for the next generation of landscape …

09 Mar

Weekly international landscape, climate and urban design update

Monday 9 March

This is your weekly international snapshot of what’s happening across landscape architecture, climate adaptation and urban design. Drawing on credible …

Events calendar

Full 2026 calendar